Paying it forward: Why we need YOU to give blood - Part 3

In this six-part series, Dr. Jeannie Callum, a hospital-based transfusion specialist, shares her real-life experience witnessing the impact of blood donation on patient lives. She provides some fascinating insight into blood transfusion, past and present, and emphasizes the need for male donors and why some donors may be safer for patients.

- Part 1: A miraculous gift, ready and waiting

- Part 2: Not your average bank

- Part 3: Blood type hype

- Part 4: Beyond matching ABO and Rh: Rare blood challenges and international cooperation

- Part 5: All blood is not the same

- Part 6: My own donation journey...

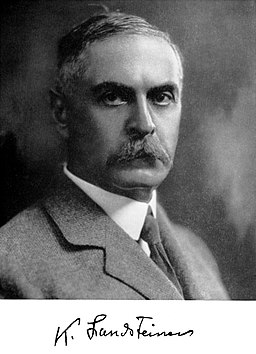

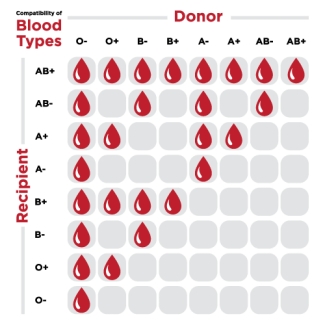

A lot of people are fixated on their blood group and what it means for their health. Some people even eat certain foods based on their blood type. To prevent transfusion complications, two key blood groups are very important to match. The first is the ABO blood group system. The ABO are carbohydrate (sugar) antigens that decorate our red blood cells. About 100 years ago, Dr. Karl Landsteiner (1868-1943) discovered this antigen. Approximately 45 per cent of us are group A and 45 per cent are group O, with the other 10 per cent being the less common groups B and AB. If you give group A blood, in error, to a group O patient, you run a good chance of killing them.

Humans all started as group A+. Frankly, if you are any other blood type you are a mutant, or as I like to think of my O- self, more highly evolved. Hundreds of thousands of years of competition on this planet with our foe, the malaria parasite, has driven this antigen off of our red blood cells. In the “malarial belt” of sub-Saharan Africa, 80 per cent of people are group O. There are unexplained disease prevalence differences between group O and A individuals. Group O individuals have lower rates of stomach and pancreatic cancer, but have higher bleeding rates.

The image to the right appears in The Conversation: Blood groups beyond ABO... Click through to read the full story. Caption: Some people from Africa lack a certain molecule on their blood cells, meaning they can’t get malaria. Artwork: The Mums by Jipil Jung (Sth Korea), Courtesy of the artist as part of Science Gallery Melbourne’s BLOOD exhibition

There was a renowned blood group rivalry between two famous English scientists, Drs. George Garratty (1935-2014) and Peter Issitt. Garratty was group O and Issitt group A. They sent papers back and forth espousing the superiority of their own blood group. Garratty sent an article finding that group O individuals had higher IQs, only to be mailed back an article from Issitt describing the resistance of group A individuals to the Plague with an attached note, “A lot of good your high IQ is going to do when the Plague comes back.”

Further reading: The Conversation: Blood groups beyond ABO... Part of a series published by The Conversation Australia in collaboration with the Australian Red Cross Blood Service looking at blood: what it actually does, why we need it, and what happens when something goes wrong with the fluid that gives us life. Read other articles in the series here.

Rhesus matters

The positive “+” and negative “–” that accompanies your blood type refers to the presence or absence of the Rhesus D protein on the surface of the red blood cells. Rh is the other important blood group we need to match blood for in transfusion medicine. This protein decoration on our red blood cells is highly immunogenic. About 15 per cent of Caucasians, seven per cent of people of African ancestry, and fewer than one per cent of Asians are Rh negative — which means that they are missing this protein antigen. The entire D gene is deleted in Rh negative individuals. Historically, we really have no idea why the gene deletion happened and why it became so common. All I can say is that it creates a lot of work for blood bank technologists, and it results in having to keep eight blood group drawers instead of four.

Anti-D

As I mentioned, the D antigen is very immunogenic, meaning on first exposure the body becomes permanently immunized to the foreign protein. It causes the most havoc in pregnancy. All Rhesus D– pregnant women are injected with anti-D antibodies from donated blood. The antibodies in the donated blood hide the antigens that are on the surface of the fetus’ red cells trafficking in the mother’s blood. Without this treatment (a type of immunotherapy), D– women would destroy their infant’s blood, limiting their number of successful pregnancies. We almost never see this problem in modern times, which is a remarkable scientific achievement. It is this scientific advancement that allowed me to marry the guy I loved, without regard for his completely incompatible A+ blood group.

Stay tuned: Part 4, titled "Beyond matching ABO and Rh - Rare blood challenges and international cooperation" will be published soon. Look for it here on RED on September 20.

Canadian Blood Services – Driving world-class innovation

Through discovery, development and applied research, Canadian Blood Services drives world-class innovation in blood transfusion, cellular therapy and transplantation—bringing clarity and insight to an increasingly complex healthcare future. Our dedicated research team and extended network of partners engage in exploratory and applied research to create new knowledge, inform and enhance best practices, contribute to the development of new services and technologies, and build capacity through training and collaboration. Find out more about our research impact.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services nor do they reflect the views of Health Canada or any other funding agency.

Related blog posts

In this six-part series, Dr. Jeannie Callum, a hospital-based transfusion specialist, shares her real-life experience witnessing the impact of blood donation on patient lives. She provides some fascinating insight into blood transfusion, past and present, and emphasizes the need for male donors and why some donors may be safer for patients.

Part 2 in a six-part series by Dr. Jeannie Callum, a hospital-based transfusion specialist who shares her real-life experience witnessing the impact of blood donation on patient lives. Here she provides some fascinating insight into blood transfusion, past and present, and emphasizes the need for male donors and why some donors may be safer for patients.