Paying it forward: Why we need YOU to give blood - Part 2

In this six-part series, Dr. Jeannie Callum, a hospital-based transfusion specialist, shares her real-life experience witnessing the impact of blood donation on patient lives. She provides some fascinating insight into blood transfusion, past and present, and emphasizes the need for male donors and why some donors may be safer for patients.

- Part 1: A miraculous gift, ready and waiting

- Part 2: Not your average bank

- Part 3: Blood type hype

- Part 4: Beyond matching ABO and Rh: Rare blood challenges and international cooperation

- Part 5: All blood is not the same

- Part 6: My own donation journey...

Dr. Bernard Fantus (1874–1940) started the first US blood bank at Cook County Hospital in Chicago in 1937. Fantus did not call it the “Blood Bank”, but came up with a much more professional-sounding name, “The Blood Preservation Laboratory.” Apparently, his wife told him the name was too fussy and to call it a “Blood Bank” instead. The name stuck, not just at Cook County Hospital, but around the world.

Large hospital blood banks are staffed with a rotating team of 20 to 50 medical laboratory technologists to cover the hospital operations 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Most of the blood bank technologists have a Bachelor of Science degree and a three-year technical degree in laboratory medicine. During those three years they rotate through each of the hospital labs: microbiology (where they figure out which bug is making you sick); chemistry (where they are able to run a battery of hundreds of tests on your blood and urine); hematology (where they count the cells in your blood); coagulation (where they figure out why your blood can not clot properly); pathology (where they figure out what kind of cancer you have); and finally, the blood bank. The technologists that self-select to go work in the blood bank are an unusual group. They seem to thrive on extreme stress — If they worked on Wall Street they’d be traders.

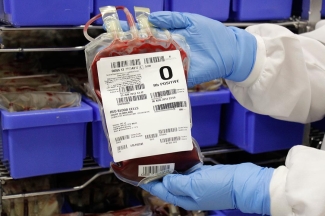

When I walk into the blood bank before a trauma has arrived or when someone has started bleeding in the operating room, it is ultra-tidy. Blood inventory stocks are at 100 per cent. At my hospital’s blood bank, we keep 80 group O units as our stock maximum and the technologists get nervous if the level drops much below 70 units.

To keep the stocks at 100 per cent, they re-order stock from Canadian Blood Services throughout the day as blood is used. They like the deck cleared and ready because a trauma could arrive at any moment. We get a call before the trauma patient arrives to let us know a bad case is coming. A technologist prepares four units of group O blood in a cooler to send to the trauma room. Group O blood is the universal donor.

Those of us who are group O bear a greater burden on the blood donation side because of emergency blood use. When the trauma arrives, if the patient is very unstable, the surgeon triggers our bleeding code, “Code Omega”. “Code Red” would be the logical code for this situation, but the Fire Department had already taken “Red”.

“Code Omega” was invented by our obstetrical colleagues to avoid announcing to everyone visiting the hospital that we have a woman massively bleeding at the time of delivery. We don’t want new grandmothers fainting when they hear the overhead announcement, “Massive hemorrhage in Labor and Delivery”. The bleeding code allows for a standardized, coordinated, and rapid resuscitation.

A dedicated porter races back and forth with cases of blood and lab samples. Special rapid blood infusers, that warm the blood, are brought to the bedside. Body warmers are used to keep the patient body temperature close to 37°C (or 98°F). Every degree drop below 37°C increases blood loss by 20 per cent. Blood doesn’t clot in the cold. The technologists prioritize this patient to the top of the list. The CT scan technologist (to figure out how extensive the injuries are), the angio suite physicians and nurses (where specialized radiologists inject glues into leaking blood vessels), and the operating room get prepped for the patient arrival.

During a trauma or “code omega” resuscitation, blood bank technologists go into almost-silent team work mode. One techonologist starts testing the patient’s blood sample. We need to turn around the testing fast as we cannot afford to deplete the group O blood stocks. By testing we can get the patient onto their own blood group if they are A, B or AB, otherwise we risk running out of group O blood. Another technologist packs the trauma stock blood into a cooler to keep “four pints ahead” at all times. (Code Omega infographic courtesy of Sunnybrook Research Institute)

The clinical team knows they don’t need to call ahead; they know the next case of blood is always ready. Another technologist gets the AB plasma (the universal donor type for the liquid part of the blood that contains the clotting factors) and places it in the plasma thawer — a warm water bath that shakes the frozen plasma up and down to speed up the thawing process. The team grabs 10 units of a product called cryoprecipitate that is enriched with clotting factor I called fibrinogen, a key factor to stop bleeding, and prepare that to thaw as well. While the frozen products are thawing, they label up some platelet units.

Over the four hours after a severe trauma arrives, the blood bank can expect to issue 20 to 200 blood units. Every one of these products originates from different blood donors. And, the blood bank goes through this routine many times a week.

Stay tuned: Part 3, titled "Blood type hype" will be published soon. Look for it here on RED on September 13.

In case you missed Part 1: A miraculous gift, ready and waiting

Canadian Blood Services – Driving world-class innovation

Through discovery, development and applied research, Canadian Blood Services drives world-class innovation in blood transfusion, cellular therapy and transplantation—bringing clarity and insight to an increasingly complex healthcare future. Our dedicated research team and extended network of partners engage in exploratory and applied research to create new knowledge, inform and enhance best practices, contribute to the development of new services and technologies, and build capacity through training and collaboration. Find out more about our research impact.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services nor do they reflect the views of Health Canada or any other funding agency.

Related blog posts

In this six-part series, Dr. Jeannie Callum, a hospital-based transfusion specialist, shares her real-life experience witnessing the impact of blood donation on patient lives. She provides some fascinating insight into blood transfusion, past and present, and emphasizes the need for male donors and why some donors may be safer for patients.