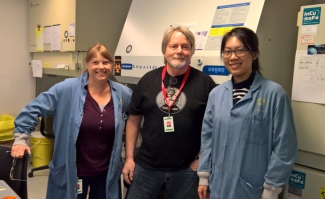

For this instalment of “Meet the researcher”, we met with Dr. Donald Branch, a scientist at Canadian Blood Services who studies infectious diseases and immunology.

How long have you been with Canadian Blood Services?

I started with the Canadian Red Cross at the Edmonton Blood Centre in December 1985. I was recruited there by the medical director, Dr. Jean-Michel Turc, to do a PhD in the department of immunology at the University of Alberta and to use my expertise in transfusion medicine as a consultant for the researchers and staff at the Edmonton Centre.

After completing my PhD, I moved to a position as a scientist at the College Street Blood Centre under the supervision of Dr. Roslyn Herst. When Canadian Blood Services took over as the blood supplier for Canada (Quebec excepted), I remained a scientist within their Research and Development division. Presently, I am the "grand old man" within the Centre for Innovation as, all told, I have spent more than 32 years working in blood services in Canada.

What’s your role?

My role within the Centre for Innovation has been, since the beginning, a discovery scientist. I am an eclectic biomedical research scientist with a curiosity for unraveling the mysteries of nature. My expertise in HIV, molecular signalling, blood transfusions and immunology helps Canadian Blood Services provide the safest blood possible. I‘m a certified specialist in blood banking (SBB) and radiation safety officer (RSO), which allows me to support the operational activities of Canadian Blood Services.

Where is your lab?

I have three laboratory spaces. One is at the Canadian Blood Services' College Street Blood Centre in Toronto, one is at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute, and one, a laboratory for working with potentially dangerous viruses and bacteria, is at the University of Toronto.

Tell us about your area(s) of research.

Projects in my labs include:

- Investigating the HIV infection process with the aim to discover new cellular targets that could be used to design alternative therapies for HIV/AIDS. We are also studying drugs currently approved for use in other diseases, such as cancer, to determine whether those drugs could be repurposed for the treatment of HIV/AIDS.

- Clarifying the roles of the signalling molecules SHP-1 and c-SRC in cancer and HIV infection.

- Learning more about how intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) is used to treat autoimmune diseases, with the goal of developing new alternative therapies. In this regard, we are collaborating with a company to test recombinant (lab-generated) proteins that are as effective as, or more effective than, IVIg.

- Helping hospitals select the safest donor blood for transfusion using a test that I pioneered in the 1980s called the monocyte monolayer assay (MMA).

What are you working on now?

- Comparing the efficacy of IVIg and a recombinant protein for treating the autoimmune disorders immune thrombocytopenia and rheumatoid arthritis, using mouse models for these human diseases.

- Examining whether we can modify IVIg to increase its safety.

- Studying the signalling molecules important for HIV to infect T-cells (immune cells).

- Continuing to optimize the MMA for use as a clinical diagnostic test.

- Investigating the role of the immune system in red blood cell death.

Further reading

RED blog post: The wonder drug you’ve probably never heard of – yet

RED blog post: Through the Microscope: monocyte monolayer assays

Why did you get into science?

I was born and raised in the Napa Valley in California. As far back as I can remember, I had only keen interest in science: dinosaurs, cloud chambers, plants and animals. With my first Gilbert Chemistry set in hand when I was around four years old, I drove my parents crazy with chemical reactions; I learned about saltpeter, sulfur and charcoal early on. During middle school, I obtained the first rocket launching permit in the Napa Valley, which drove my father nuts. He was afraid I would start a fire with my rockets and rocket fuel, which I made myself from zinc dust and sulfur. In high school, a special class was organized, just for me and one other person in the school, for doing special science experiments without direct supervision. We were told it would cost too much to make a rocket propelled go-cart, so we decided to produce a very pure laughing gas — just before physical education class.

While majoring in chemistry in university, I was approached by Andre Tchelistcheff (now considered one of the world’s greatest winemakers) to be his winemaker apprentice, but in the late 1960s I wasn’t interested in wine making. Instead, I was focused on winning a Nobel Prize in chemistry. So, rather than becoming a world-famous winemaker, I kept my focus on science and it's been a great ride. I first got into science more than 60 years ago and my interest in science hasn’t waned.

What inspires you?

Serendipity inspires me. Great science and scientists inspire me. Scientists such as Linus Pauling and Albert Einstein are my heroes. I’ve met several scientists who have won a Nobel Prize for their work in medicine and physiology, and these individuals inspire me not only because of their major discoveries and their imaginations but also because of their humble natures.

What do you find most exciting about your work?

The most exciting part of science is that when you do good science, you get more questions than you get answers, which means it is never boring. It is always exciting, especially when you discover something solely by accident (or serendipity). I also appreciate that a hypothesis cannot be proven. You can only disprove an idea. There is no end to imagination; new ideas, theories, experiments and discoveries occur often and provide a level of excitement to which many other professions cannot attest.

What work are you most proud of?

I am proud of all my work but my discovery of mixed hematopoietic chimerism is one that I am most proud. Mixed hematopoietic chimerism occurs when a stem cell transplant recipient’s original stem cells regrow despite being irradiated before the transplant. This causes the patient to have a combination of blood cells with different genetic backgrounds: some generated by the recipient’s original stem cells and some from the donor’s transplanted stem cells. Mixed hematopoietic chimerism can be a sign that the leukemia has relapsed; however, it also creates immune tolerance to prevent the transplanted stem cells from attacking the recipient's tissues. Because of this immune tolerance effect, many researchers are currently trying to induce mixed hematopoietic chimerism in patients awaiting solid organ transplants.

My invention of a reagent that modifies red blood cells for use in antibody testing made me quite proud; this reagent is now sold commercially and used in transfusion labs throughout the world. My pioneering work with the MMA over the years has also given me great pride, as well as a few awards.

Most importantly, I am very proud of the many students (high school, undergraduate and graduate), postdoctoral fellows and medical doctors that I have mentored over the years. Also, the various colleagues and collaborators, technicians and other staff that I have been lucky to know and interact with are a source of great pride for me.

When you’re not in the lab where could we find you?

I’m a news junkie, so you can find me watching CNN at home with a glass of fine California cabernet. You may also find me cooking something tasty. With a Swiss–Italian background, plenty of garlic and wine goes on the meats and into the sauces.

Subscribe to the Research & Education Round Up to stay up to date on research publications and funding opportunities.

Visit our Funded Research Projects page to view projects funded by Canadian Blood Services.

Canadian Blood Services – Driving world-class innovation

Through discovery, development and applied research, Canadian Blood Services drives world-class innovation in blood transfusion, cellular therapy and transplantation—bringing clarity and insight to an increasingly complex healthcare future. Our dedicated research team and extended network of partners engage in exploratory and applied research to create new knowledge, inform and enhance best practices, contribute to the development of new services and technologies, and build capacity through training and collaboration. Find out more about our research impact.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services nor do they reflect the views of Health Canada or any other funding agency.

Related blog posts

Wonder drug it may be, but IVIg is a slippery fish. Even after 60 years, little is known about precisely how it works. An encounter with a scientist The first thing you notice when you walk into Dr. Don Branch’s office at 67 College Street in Toronto is how small it seems. And colourful, owing to an...