By Lisa Bendall, Health Writer

This feature article was originally published in the Canadian Journal of Medical Laboratory Science (CJMLS) in Summer 2016. The CJMLS is a publication of the Canadian Society of Medical Laboratory Science. Please note that clarifications, updates and some additional content have been added (see italics) by Canadian Blood Services. Also note that within this article transfusion service providers (Canadian Blood Services' customers) are described as blood banks, banks, transfusion labs, hospitals and regional health authorities.

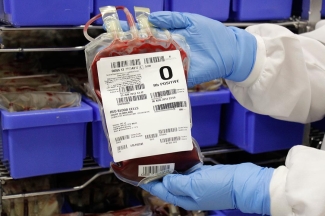

Most days, across Canada, blood is on the move

It’s expected that our population will need nearly a million units of donated red blood cells this year. It’s undeniably gratifying to be a link in the lifesaving supply chain, as any donor or transfusion specialist will probably tell you. But what happens when the blood supply is critically low and not every patient can quickly get the components they need? How does the health care team make challenging ethical decisions?

Most of the time, the blood banks of hospitals across Canada are sufficiently endowed. Canadian Blood Services (or Héma-Québec, in that province), which manages the collection and supply of blood, is in daily contact with hospitals and (regional) health authorities across the country to review their inventory levels and resupply needs.

“We move inventory almost every weekday,” says Rick Trifunov, Director of the Supply Chain Operations Planning Group at Canadian Blood Services. “We’re constantly trying to make sure that things are level-loaded and we’re not skewing toward shortage anywhere.”

Transfusion labs (in hospitals) make inventory requests based on what they have in stock and what cases are coming up, such as a full-term pregnant mother with a rare blood type. No hospital wants to find itself short on blood in a crisis. But neither would it be ethical to overstock on products that will expire before they’re used, or to deprive patients at other hospitals.

"It’s a daily balancing act," says Shelley Solomon, a Medical Laboratory Technologist at Mount Sinai Hospital’s Blood Transfusion Services department in Toronto. “We have a level which we’re supposed to keep the blood at, but sometimes we might ask for a bit more, because we don’t want to run out in an emergency. When you’re working by yourself [at night], the last thing you want to see is that the bank’s empty.”

No one can predict what tomorrow will bring. Despite its best efforts, a hospital’s blood bank may prove inadequate. In 2014, the blood transfusion laboratory at Toronto’s University Health Network (UHN) was left scrambling when two patients with the same rare IgA deficiency both needed blood on-hand for unexpected surgery. Since just one in 700 blood donors shares this rare deficiency, Canadian Blood Services was unable to deliver compatible blood in time.

In the end, the UHN blood transfusion team and Canadian Blood Services worked together to prepare “washed” blood — the Canadian Blood Services production department removed most of the IgA protein from regular donor units. Often, though, hospitals in busy urban centres have a special advantage when they run low without notice: they can do a little red blood cell swapping, instead of waiting for a resupply from Canadian Blood Services. “We are fortunate to have neighbouring hospitals around us, that have even bigger supplies than we do, as a resource,” says Solomon. It works both ways. “If we see something getting close to expiry, we can always hand it off to a trauma centre that can use it quickly, instead of it dying on our shelves.”

That swapping strategy won’t work everywhere. For Queen Elizabeth Hospital on Prince Edward Island, the next-closest hospital is in Moncton, three hours away. The nearest Canadian Blood Services (distribution site) is five hours away.

“We’ve had trauma patients where we’ve had to wait for more blood to arrive, where the bank is depleted,” says Georgette Turner, Chief Technologist at the PEI Transfusion Service Lab. “Our biggest concern is always a storm and how we’d get the shipment here. We’re more concerned about the logistics of transportation than shortages.”

Fortunately, Turner has a procedure to follow: If she observes that inventory is running low, she immediately puts in an order for more. Outside regular delivery hours, a medical taxi is set up to make the drive. Blood products can also be flown in by Air Canada if timing is critical.

“Canadian Blood Services makes every effort to get it to us,” Turner says. “We’ve never had to say no to someone [in need of transfusion].”

What if the blood shortage is national and there isn’t enough product available anywhere in Canada to redistribute where it’s needed?

“We’re normally in a favourable inventory position,” says Rick Prinzen, Chief Supply Chain Officer, “but there are rare occasions where the national inventory has dropped to levels that are less than desirable.” In January (2016), Canadian Blood Services declared an Amber Phase for platelet inventory levels.

An Amber Phase is called when the blood component supply is not high enough to meet all routine patient needs; a Red Phase means it’s insufficient even for patients who need non-elective transfusions.

Canada has never reached a Red Phase which would likely be triggered by a combination of misfortunes such as labour strikes, pandemics, extreme weather, and a catastrophic failure in the supply chain.

“Typically, it’s not going to be just one thing,” says Trifunov. In the case of January 2016’s Amber Phase, blood donations had fallen off because of the New Year’s holiday weekend, while demand unexpectedly rose. That Amber Phase lasted just 36 hours. “That reflects the effectiveness of all hospitals taking similar steps to manage a supply,” notes Prinzen. “It was quite effective to get us through that low-inventory period.”

Inventory phases in Canada are determined by the National Emergency Blood Management Committee (NEBMC). They develop recommendations and provide advice to the Provincial/Territorial Ministries of Health, hospitals/Regional Health Authorities and Canadian Blood Services to support a consistent and coordinated response to critical blood shortages in Canada. The NEBMC includes individuals from the groups noted above and is led by the current chair of the Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products (NAC).

Prior to declaring a blood shortage phase, the NEBMC takes a number of factors into consideration. This not only includes Canadian Blood Services’ collection/recovery capacity and national inventory but also hospital inventory, as typically the majority of Canada’s blood supply is held within hospitals at any given time.

All hospitals and (regional) health authorities must have an emergency blood management committee, with reps from several departments, including an MLT in the transfusion service lab who can report on the current blood inventory and discuss what options are available. In the case of an Amber or Red Phase, these committees will ensure their facilities are adhering to a national (blood shortages) management plan. That way, every hospital is handling the shortage the same way, making the same clinical decisions that have been carefully worked out ahead of the crisis.

In 2009, the NAC and the Canadian Blood Services jointly created a plan to maximize the effectiveness of a national response to any crisis which impacts the adequacy of the blood supply in Canada. The current plan, titled The National Plan for the Management of Shortages of Labile Blood Components (or The National Blood Shortages Plan) is available at the NAC website.

“It’s that whole concept of trying to do more equitable distribution of a national resource,” says Dr. Susan Nahirniak, who is a member of the National Emergency Blood Management Committee, and has worked on The National Blood Shortages Plan (Dr. Nahirniak is the chair of a working group that makes revisions to this plan). “It makes everybody treat their patients and their inventory the same.” For example, during an Amber Phase, the national plan dictates that hospitals cancel elective surgeries and adjust their optimal inventory levels. Units may be split to benefit more patients, or even used past their expiry if it’s medically justified.

During a Red Phase, when resources are strictly rationed, hospitals with massively bleeding patients have a triage tool to guide complex decision-making over ‘who gets what first’.

“This is what I go through on a fairly regular basis as a transfusion medicine physician,” says Nahirniak, who practises in Edmonton. She recalls trying to help a patient on ECMO (cardiac/respiratory life support). “We couldn’t get control of the bleeding. It was just continual request for product after product. We weren’t in Amber Phase, but we were not with a robust inventory here locally.” If she continued transfusions, she’d be putting other patients in jeopardy. Nahirniak was obliged to gather the patient’s medical team, and together they assessed the likelihood of survival with a good outcome.

This demonstrates the importance of having a framework to follow during a potential Red Phase blood shortage, one that reflects careful thought, and extensive consultations with all stakeholders. In a country-wide crisis, no one, including MLTs, would be forced to make weighty ethical decisions alone.

Nahirniak would like to see improved awareness that the national plan exists. After every simulation or real-life shortage situation, her advisory committee conducts a review and revises the plan.

“In our platelet Amber Phase in January (2016), we identified some problems with communication. There’s still some misunderstanding of what the plan is trying to achieve and what the parameters are in there,” she says. She’s concerned, for instance, that technologists who aren’t very familiar with the protocols might be uncomfortable issuing expired platelets. “That has caused some angst with MLTs in the past.”

A strong, communicative team makes a difference. Although PEI’s Turner has never had to apply the Red Phase framework, she’s confident she and her colleagues would follow it closely. “Our medical director would have a good handle on it, and we have good communication here between technologists and the medical director,” she says. “I would have absolutely no concerns.”

Nahirniak’s group, meanwhile, is continuing to lead workshops and simulation activities. “We need that awareness so that the plan can happen seamlessly,” she says. “Sometimes those lessons learned, when you’re in those shortage situations, it doesn’t connect. If we can get better understanding, I think we’ll be more successful in a potential or true shortage.”

Canadian Blood Services is continually focused on ways to better manage, and most importantly avoid, severe blood shortages in Canada. Not only does Canadian Blood Services participate in Dr Nahirniak’s working group, we are always looking at ways to improve our own processes, external communication mechanisms and education materials. Recent improvement initiatives and areas of focus include: development of our own blood shortages plan, a more comprehensive inventory monitoring system to identify and avoid shortages, enhanced holiday collection/production planning, more effective inventory levelling across Canada, targeted donor recruitment activities, sharing of best practices around inventory management and utilization, better understanding of hospital inventories and demand through enhanced mechanisms for hospital reporting, assisting in hospital inventory optimization, and preventable discard reduction, to name a few.

From widespread education about a national management plan, to ongoing discussions among health care team members, to regular dialogue between hospital sites and Canadian Blood Services locations, it’s clear that communication puts every stakeholder on the same page. Ultimately, it is how we’ll all be protected in the event of a nation-wide blood crisis.

References:

- Canadian Blood Services, Blood

- National Advisory Committee on Blood & Blood Products and Canadian Blood Services, National Plan for the Management of Shortages of Labile Blood Components

- National Advisory Committee on Blood & Blood Products, Emergency Framework for Rationing of Blood for Massively Bleeding Patients during a Red Phase of a Blood Shortage

We are very grateful to the author Lisa Bendall and the Canadian Journal for Medical Laboratory Science for allowing us to republish this article.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services nor do they reflect the views of Health Canada or any other funding agency.

Related blog posts

In this six-part series, Dr. Jeannie Callum, a hospital-based transfusion specialist, shares her real-life experience witnessing the impact of blood donation on patient lives. She provides some fascinating insight into blood transfusion, past and present, and emphasizes the need for male donors and why some donors may be safer for patients.

Part 2 in a six-part series by Dr. Jeannie Callum, a hospital-based transfusion specialist who shares her real-life experience witnessing the impact of blood donation on patient lives. Here she provides some fascinating insight into blood transfusion, past and present, and emphasizes the need for male donors and why some donors may be safer for patients.