‘It’s like everything went from black and white to colour again’

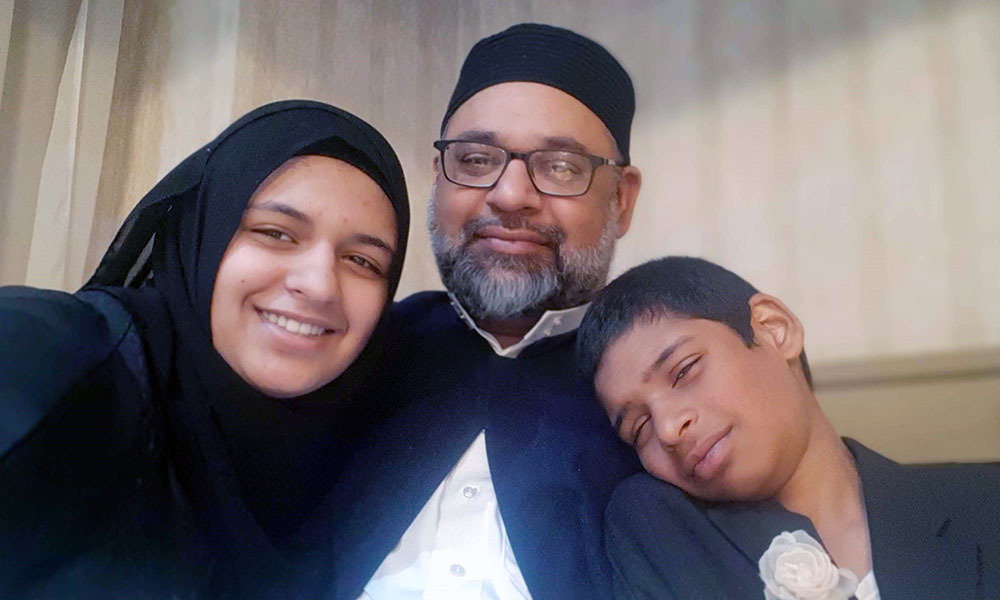

A kidney donor made all the difference for Shariq Khan, a college professor and spiritual leader in Barrie, Ont.

Shariq Khan knew from a young age that his health was fragile. He watched his father go through kidney failure because of hereditary nephritis, a condition they shared. But when his own kidneys failed in April 2011, it was still a huge shock.

“I went in for my yearly blood test and they said, ‘Go to the hospital right away,’” recalls Shariq, a professor in the mechanical engineering program at Georgian College in Barrie, Ont. “My dad didn’t need dialysis until he was in his fifties. I was in my thirties.”

Dialysis, which does the work of the kidneys by mechanically filtering the blood to remove waste products and extra fluid, became essential to his survival. But it also required several hours-long visits to hospital each week. There were three at first, then five to six. Sometimes he also needed blood transfusions during his sessions.

With two young children at the time, it was a difficult juggling act for Shariq and his wife. As well, travel abroad — a big part of Shariq’s adult life, for both his teaching career and his study of Islam — was put on pause.

“You can’t go around the world when you’re on dialysis,” says Shariq. “Our life changed quite a bit in terms of how it was before.”

The wait for a kidney transplant

Shariq’s only alternative to dialysis was a kidney transplant. But while several friends and family members went through testing to become a living kidney donor for him, none were eligible to proceed. He would need to wait for a deceased organ donor. At any given time, about 4,000 people in Canada are waiting for an organ, and like Shariq, 80 per cent of them require a kidney.

Unfortunately, too few people register as organ donors to meet the needs of patients. Although 90 per cent of people in Canada say they support organ donation, fewer than a third actually register. The result is that each year, approximately 250 people die waiting for an organ transplant. That includes many people on dialysis.

Shariq was fortunate that after a year and a half of dialysis in hospital, he was able to install equipment at home to filter his blood overnight as he slept (home hemodialysis). Colleagues and friends renovated his basement to accommodate the machine and make the space comfortable for his nightly treatments. He was grateful for their support, and that of his family.

“It took about an hour to set up the machine before going to sleep,” Shariq remembers. “My daughter was three or four years old, and she’d come and help me. She’d hug me and go to sleep on my chest sometimes.”

But even nightly dialysis couldn’t fully compensate for his lack of kidney function.

“It just wears you out,” he says. “You have pain. You have days where you just can’t get out of bed.”

A kidney donor makes all the difference

While on dialysis, Shariq continued to work, as well as give sermons and teach classes at the Barrie Mosque. The low energy and pain simply became normal.

“I was doing a lot, but I was really on autopilot,” Shariq says. “The growth wasn’t happening — the spiritual and intellectual growth.”

So after nearly four years of dialysis, in December 2014, Shariq felt “blessed” to receive an incredible gift: a kidney from a deceased organ donor.

“I didn’t realize what I was really going through until after I had my transplant,” he says. “It was like everything went from black and white to colour again.”

Within ten days of the operation he felt completely rejuvenated.

“Everyone said, ‘You look so much better. You have colour in your face.’ It was almost like flipping a switch.”

A chance ‘to move, to live, to connect, to grow’

That kidney donor has helped Shariq make new, treasured memories with his family. He’s enjoyed weekly visits with family in Toronto, and skateboarding and trips to the beach with his son, who is now 11, and his daughter, who is now 14.

He’s also been able to help many more engineering students launch careers, and to expand his role as a spiritual leader. Since 2018, Shariq has been the imam at the Bradford Islamic Centre. His improved health allows him to provide guidance further afield as well.

“Someone invites me to give a sermon somewhere and I’m like, ‘Yeah, I can travel overnight, meet with your community,” Shariq says.

The second chance represents “the ability to move, to live, to connect, to grow.” And it compels him to honour his donor’s generosity by serving others.

“There are so many opportunities to do good in the world, and to spread beauty in the world, that I didn’t have the capacity to do before the transplant,” Shariq says. “I’m cognizant of what that person gave me. I’m supremely grateful to them and I want to do good so as to show gratitude to that person.”

“I’m responsible now for that gift. I have to do something with it.”

Exploring Islam and organ donation

His service includes sharing his experience with the broader Muslim community, to encourage others to think about registering as organ donors.

“I’m not saying, ‘you should’ or ‘you shouldn’t’; it’s your body,” Shariq says. “But at least think about this reality, and the opportunity to do a great deal of good even after you pass away.”

There are differences of opinion among Muslims about organ donation and deciding to donate is a very personal matter. That’s why Shariq worked with another imam to produce a pamphlet about Islam and organ donation for Ontario’s Trillium Gift of Life Network.

Organ donation is a numbers game

The more people choose to register as organ donors, the more lives can be saved. Only a small percentage of people die in such a way as to make it possible for them to become organ donors, so it takes many registrants to meet the need. And while donated organs are not matched based on race or ethnicity, it’s also important to have a diverse donor pool. Organ donors and recipients need to have compatible blood types and certain tissue markers in common, and similar ancestry boosts the likelihood of a match.

A kidney from a deceased organ donor lasts on average from 10 to 15 years. As Shariq heads toward the ninth anniversary of his own transplant, he knows he is likely to need another some day. For now, with the gift of time he’s been given, he’s making every moment count.