Blood in war zones: Canada’s contributions and ongoing support for soldiers who need transfusions

By Andrew Beckett

Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Beckett, MD is the chief of general surgery and trauma advisor to the Surgeon General of Canada.

You rarely see the types of injuries I saw in Afghanistan among civilians. High-velocity ammunition. Fragmentation grenades. Land mines and improvised explosive devices. When someone is massively bleeding, they need blood. No matter how good a trauma surgeon may be, without blood, people are going to die. Canadian Blood Services is a vital partner in ensuring blood and blood products are there for trauma patients, even in the remote and dangerous environments that are often the setting for military operations.

Early innovations

|

Image

|

Image

|

Canada has been a major player in battlefield blood transfusion since the First World War. At the time, the popular response to severe blood loss among British doctors was injecting saline solution. This would increase the volume of the blood but would often result in a rapid decline soon after because the diluted blood couldn’t restore normal functions of the wounded soldier. Dr. L. Bruce Robertson, who during peacetime worked at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto as a surgeon, was a pioneer in transfusion medicine who brought his knowledge and skill to the front line.

|

Tourniquet from the First World War (CWM 20100106-038/ Canadian War Museum) |

Arriving at casualty clearing station from the Front in October 1916. (Library and Archives Canada/C-3395813) |

Robertson would draw blood from soldiers with relatively minor injuries at his casualty clearing station and transfuse it into trauma patients who needed it. The Royal Army Medical Corps would go on to describe his influential work as “the most important medical advance to come from the First World War.”

|

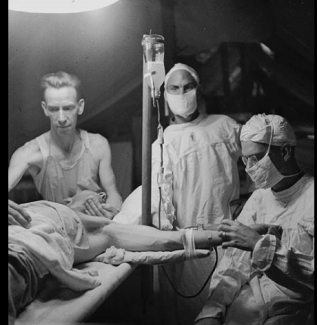

Norman Bethune performing a transfusion (Library and Archives Canada/C-67451) |

Refugees beside an ambulance of the Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit during the Spanish Civil War. (Library and Archives Canada/C-3194605) |

Another Canadian of note in battlefield transfusion was Dr. Norman Bethune, who during the Spanish Civil War used his knowledge in transfusion to create the first front-line mobile blood transfusion unit. The vehicle included a fridge, a sterilizer and an incubator. Five months after it began in 1937, his Servicio Canadianse de Transfusion de Sangre Al Fiente supplied blood across the 1000-km front. It provided up to 100 transfusions a day, and quickly grew from one vehicle to a fleet of five. To supply the front lines, Bethune also created a blood donor centre in Madrid where a pool of donors could be called upon every three weeks to donate. By the end of the war in 1939, the service had transfused around 5,000 units of blood. Bethune’s unit was responsible for about 80 per cent of all transfusions during the Spanish Civil War.

Research and development: Freeze-dried plasma

Plasma can be very useful in treating blood loss, but it wasn’t the most practical option because it has to be frozen, and once thawed (which takes about 30 minutes), has to be refrigerated then used within a week. In wartime conditions where surges of trauma patients can come unexpectedly, frozen plasma isn’t always the most practical option. This is especially the case in remote environments where access to freezers, fridges, or thawing equipment is limited or non-existent.

|

Lieutenant B. Rankin, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, administering a blood transfusion to a wounded soldier, Montreuil, France, 10 September 1944. (Library and Archives Canada/C-3395950) |

Glass bottle of dried blood plasma serum and the metal case in which it travelled, labelled July 25, 1945. (Canadian Red Cross) |

In the Second World War, Charles Best, half of the insulin-discovering duo Banting and Best, was a leader in developing freeze-dried plasma. Plasma was dehydrated in bottles that were then sealed and shipped. It could then be rehydrated with sterile distilled water as needed and transfused to patients. This made plasma lightweight and long-lasting, meaning greater access to a lifesaving product. Canada became the lead producer of freeze-dried plasma in the Commonwealth.

By the Korean War, freeze-dried plasma use was waning because the way it was made from the pooled plasma of many donors, and the lack of effective tests for certain diseases, meant it was infecting soldiers with hepatitis. In the decades since, the medical and biopharmaceutical community has lost a great deal of expertise in this area. But,what’s old is new again — new and improved testing and screening processes have led to a renewed interest in freeze-dried plasma in the military community in recent years, including a new Canadian military research collaboration to redevelop this product at Canadian Blood Services.

A walking blood bank

Beginning in 2006, the Canadian Armed Forces partnered with Canadian Blood Services to create the Walking Donor program, essentially a walking blood bank. It was created during the Afghanistan War when a large deployment of Canadian troops was headed to Kandahar. It provided a way to access blood products, such as red blood cells and plasma, where they wouldn’t otherwise be readily available.

The Walking Donor program pre-assesses troops before they’re deployed for future consideration as blood donors during deployment. The troops go into Canadian Blood Services donor centres for screening and testing, including health screening, transmissible disease testing and blood typing which Canadian Blood Services uses in its regular donor programs.

The pre-assessment information is available to military medical personnel, who can choose donors based on eligibility in cases where casualties need a blood transfusion. The donor then gives whole blood to be administered to the casualty. The Surgeon General authorizes the use of fresh whole blood in an operational environment, and after the transfusion both the recipient and donor receive testing to ensure safety. As part of this program, Canadian Blood Services also trains Canadian Armed Forces personnel in screening and phlebotomy.

That partnership closed in 2009, then resumed in 2014. Canadian Blood Services provides ongoing support through the Walking Donor program, and since 2006 has screened approximately 2,800 members of the Canadian Armed Forces prior to deployment.

Arm-to-arm: coming full circle

Transfusion medicine has taken great strides since the First World War, but in one big way transfusion in military operations is coming full circle. Canadian Blood Services is exploring bringing back whole blood as a product, reprising the arm-to-arm transfusions of earlier days. The modern gold standard in transfusion medicine is component therapy, meaning people are transfused with the blood components they need — red blood cells, plasma, or platelets. In trauma patients who have suffered substantial blood loss, whole blood gives people the blood they need in the proportions they need to stave off blood failure — to keep their hearts beating, their lungs breathing, to give our soldiers a fighting chance.

In cases like this, only blood and blood products will work. Canadian Blood Services plays an essential role in our ability to provide the best care possible when we’re overseas.

Andrew Beckett CD MD MSc FRCSC FACS is a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Royal Canadian Medical Services and serves as a trauma surgeon and critical care physician. Dr. Beckett is also a trauma surgeon at Montreal General Hospital. He has served on multiple military missions overseas.

His research interests include massive transfusion and resuscitation in the austere setting, combat casualty database management and military simulation training. He is currently an assistant professor of surgery at McGill University.