Hemochromatosis and why blood loss can be a beneficial form of therapy

Wednesday, May 04, 2016 Michelle Hampson

May is National Hemochromatosis Awareness Month.

Blood plays a vital role in our bodies, circulating essential nutrients from the core organs to our extremities and back again. Instinctively, some panic when they cut themselves and see this life-giving liquid escape, even in tiny amounts.

Yet, for a few, loss of blood can be a beneficial form of therapy.

What is hereditary hemochromatosis?

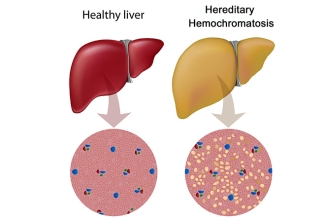

Hereditary hemochromatosis is a relatively common genetic condition where the body stores more iron than normal. It occurs most commonly in people of northern European descent, affecting 1 in 300 people of this demographic. Iron is a central component of our blood – we can’t live without it. However, we only need a few grams for our blood to function normally. Excessive levels of iron can be toxic.

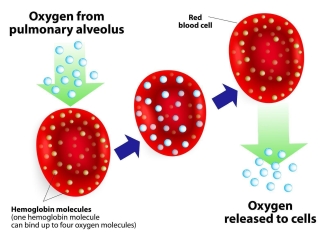

Iron is taken into our bodies (absorbed) by specialized cells in the small intestines, called enterocytes, which extract it from the foods we eat. Iron is then used to create an essential molecule that attaches to red blood cells to help transport oxygen, called hemoglobin, or it is stored in cells as ferritin. Iron homeostasis is a delicate balancing act that ensures adequate supply while limiting excess uptake. Iron is only lost through sloughing of skin, mucosal cells and blood loss as there is no regulated means of excreting excess iron.

If the body takes in too much iron, it can accumulate in vital organs. The liver is most commonly affected and iron accumulation can cause tissue scarring that impairs the liver’s important role in filtering toxins from the body. The heart and pancreas are also at a higher risk of damage.

Although hereditary hemochromatosis is caused by genetic mutations, not all people with the genetic mutations develop the condition. And, not all people with the condition show symptoms. Testing the amount of ferritin, a protein that binds iron in the body, is an indirect measure of body iron stores. This test can help determine whether additional testing is indicated for diagnosing hereditary hemochromatosis.

Youtube video via Osmosis.

For those diagnosed with hemochromatosis, one way to reduce the excess iron is to limit eating foods or taking vitamin supplements that contain iron. But, the most effective treatment is to remove blood from the body. This type of therapy is called phlebotomy.

How does phlebotomy help?

Much of the iron in our bodies is in our red blood cells, so removing blood from the body helps get rid of some of the iron. But it can also help remove some of the excess iron that has accumulated in other organs.

When the body senses that there is lower than normal amounts of blood, it kicks into gear to produce more. Not enough blood? No problem! The kidneys first sense a need for more blood, causing them to release a protein that prompts bone marrow to start producing more. Macrophages, cells that are part of our immune system, then seek out extra stores of iron. Most often iron is stored in the liver, but macrophages can collect iron stored in other areas as well. These specialized immune cells then deliver the mineral to our bone marrow, which it uses to produce more blood.

So, removing blood and putting the iron to work to make more blood can help gradually reduce excess levels of iron in the body.

How effective is phlebotomy for treating hemochromatosis?

Each patient is diagnosed with different levels of iron in their body, and so people may need regular phlebotomy treatments for different periods of time. But overall, phlebotomy, a treatment that makes use of the body’s natural blood production process, is quite effective.

Dr. Michelle Zeller, a medical consultant with Canadian Blood Services, is a clinical hematologist who treats blood disorders. She says, “So far, all of my patients with hemochromatosis have eventually responded to phlebotomies – though it can sometimes take 1 to 2 years of weekly treatments to bring the ferritin level down to target levels.”

In general, men have higher levels of iron accumulation when hemochromatosis is diagnosed, because women lose iron regularly through their menstrual cycle. It sometimes takes longer to decrease the ferritin levels in men, or in postmenopausal women. Doctors tailor phlebotomy schedules based on each patient’s iron levels, as well as other factors.

For example, iron is a key part of hemoglobin, the component in blood cells that carries oxygen. It’s important that people have sufficient levels of hemoglobin. So doctors take into account a patient’s hemoglobin levels when recommending a phlebotomy schedule.

If hemoglobin levels within the blood become too low (a condition called anemia), this can result in fatigue and other symptoms, which doctors are careful to avoid.

“If the patient’s hemoglobin is not maintained at a reasonable level after the phlebotomy (I often target 125 g/L), I can either increase the interval between phlebotomies or decrease the amount taken out at each phlebotomy,” explains Dr. Zeller.

The gradual process of phlebotomy can effectively extract iron from the body of people with hemochromatosis, preventing further damage to vital organs. Some evidence even suggests that phlebotomy can reverse early tissue damage (fibrosis) in the liver. Often phlebotomies are done weekly until ferritin levels reach the target level.

“If a person with hemochromatosis is otherwise eligible, they can become a regular donor at Canadian Blood Services. Many healthy hemochromatosis patients find it a much more comfortable environment for lifetime maintenance phlebotomy treatment; not only is it therapy, but also it provides much needed blood for other Canadians. Blood donations can be made every 56 days (for men) or 84 days (for women), provided the hemoglobin is normal and the patient is not on insulin.”

Phlebotomy provides therapeutic benefit to people with hemochromatosis, but also has the potential to benefit other people who are in need of a blood transfusion as well. If patients with hemochromatosis meet eligibility criteria, they can donate through Canadian Blood Services every 56 days (for men) or 84 days (for women).

Dr. Zeller notes that donating blood can be very helpful for her hemochromatosis patients. “They are very happy to miss out one required visit to the hospital where they have to pay for parking, wait, and sit in a hospital, and instead go to a donor clinic where their blood can help recipients in need.”

Once a person’s ferritin level is in a reasonable range, the frequency of phlebotomies can decrease. This is called maintenance therapy, which may involve phlebotomies every 3 to 4 months.

Other Reading

- The Canadian Hemochromatosis Society website: TooMuchIron.ca

- Iron basics on blood.ca

- Protecting our life blood: iron deficiency in Canadian blood donors

About Dr. Zeller

Michelle Zeller, MD FRCPC MHPE DRCPSC, is a medical consultant with the medical services and innovation division of Canada Blood Services. She is also an Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology and Thromboembolism, McMaster University and a Transfusion Medicine Specialist for the Hamilton Regional Laboratory Medicine Program. Her clinical interests include iron deficiency anemia and hemochromatosis. Her research interests include outcomes-based assessment in medical education, informed consent and blood product utilization.

Canadian Blood Services – Driving world-class innovation

Through discovery, development and applied research, Canadian Blood Services drives world-class innovation in blood transfusion, cellular therapy and transplantation—bringing clarity and insight to an increasingly complex healthcare future. Our dedicated research team and extended network of partners engage in exploratory and applied research to create new knowledge, inform and enhance best practices, contribute to the development of new services and technologies, and build capacity through training and collaboration.

About the author

Michelle Hampson is a writer who has spent years communicating medical science and treatment options to people living with chronic conditions, such as cancer and autoimmune diseases. Now based in Washington, DC, she reports on research published in the journal Science.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services.

Related blog posts

Wonder drug it may be, but IVIg is a slippery fish. Even after 60 years, little is known about precisely how it works. An encounter with a scientist The first thing you notice when you walk into Dr. Don Branch’s office at 67 College Street in Toronto is how small it seems. And colourful, owing to an...

" The ever-present need for innovative ways to combat dengue and other emerging viruses and pathogens has never been clearer."