Graduate fellow, Cindy Tong, heads to Taiwan on a CIHR Travel Program Award

Wednesday, June 08, 2016 Jenny Ryan

Ms. Tong is a Canadian Blood Services' graduate fellowship program award recipient working with Dr. Don Branch in his Centre for Innovation lab in Toronto. She has also been selected to participate in a highly competitive Canadian Institutes for Health Sciences (CIHR) Travel Award Summer Program in Taiwan. We took some time to ask Ms. Tong a few questions about her research, this prestigious award and her upcoming travels.

A Q&A with Ms. Tik Nga (Cindy) Tong

Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

I was born in Hong Kong and my family moved to Vancouver, BC when I was 8. My interest in science started at a young age, partially due to the influence of my older brother (who is also in science). This led me to pursue a B.Sc. degree in Microbiology and Immunology at UBC. As an undergraduate at UBC, not only was I exposed to the theoretical side of science, I was also part of the Science Co-op program, where I got first-hand benchwork experience in both federal and private sector laboratories.

Can you describe your experience in Dr. Branch’s lab?

When I decided to continue my education in graduate studies, I wanted to leave my comfort zone and the gorgeous city of Vancouver that I grew up in. I ended up relocating to Toronto and I got admitted into the department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at U of T. Although the search for a suitable laboratory was not a smooth and well paved path, I am fortunate to pursue my degree in Dr. Branch's lab. The Branch lab is truly a work-hard and play-hard environment, with highly motivated, friendly and helpful lab mates and fellow graduate students. And Dr. Branch's open-door policy has given me the freedom to pursue various side projects when I stumbled across interesting results, while keeping me on track of my primary thesis project.

What is your research focus?

My current research focuses on the optimization and application of an in vitro assay, monocyte monolayer assay, that can be used to predict transfusion outcomes in patients with heightened risk of immune-mediated hemolysis (e.g. Sickle cell or alloimmunized patients). Although this assay has a very narrow niche, hopefully my thesis work and our manuscript in preparation will eventually lead to the inclusion of this assay in accredited reference hematology labs in Canada.

You have received a Canadian Blood Services’ graduate fellowship award, what opportunity/experience does it offer you?

With financial support from the Canadian Blood Services graduate fellowship award, I have more flexibility in taking some detours in my research to invest in side projects. In addition, the travel allowance associated with the award offers a valuable opportunity for me to attend conferences. For example, I have recently attended and presented a poster at the Canadian Society for Transfusion Medicine (CSTM) Annual Conference 2016 in Vancouver, BC.

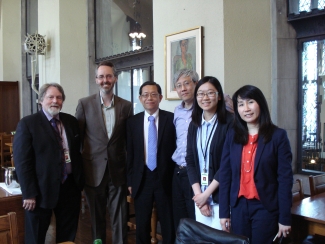

Photo (left to right): Dr. Donald Branch (Canadian Blood Services), Dr. Eric Marcotte (CIHR), Mr. Jih Shao (Science and Technology Division of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Canada), Dr. Jimmy Huang (York University), Ms. Tik Nga (Cindy) Tong, and Ms. Alicia Y.H. Wang (Deputy Director Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Toronto).

Tell us about the CIHR Travel Award Summer Program in Taiwan?

The CIHR Travel Award program in Taiwan was established to encourage collaboration and the exchange of graduate students between Canadian and Taiwanese institutions. I had read about this award in circulating departmental emails during my first year at U of T, but I waited until my final year before applying. The award application process is similar to graduate school application, where the most difficult part is identifying a supervisor. Luckily, I have been matched with Dr. Li-Chung Hsu at the National Taiwan University (NTU) located in Taipei. The 8-week summer program includes an orientation week in Hsinchu, hosted by the National Tsing Hua University, followed by 7-week of research work in host institute.

What is the joint project you’ll be working on while you’re in Taiwan?

One of the side projects I have been working on in Dr. Branch's lab involves looking at how various antibodies mediate or interfere with physiological responses after engaging the cellular receptors. The joint summer project with Dr. Li-Chung Hsu involves investigating the downstream signaling pathways after the engagement of these cellular receptors by various antibodies.

What are you looking forward to on your travels?

I will be flying to Hong Kong a few days before the start of the program, just to visit my birth city and some relatives I haven’t seen since my last visit in 2012. As I have mentioned before, I will then spend orientation week in Hsinchu and the rest of my stay in Taipei. In addition to experiencing the research environment at NTU and meeting other graduate students from Canada, US and Taiwan, I am looking forward to exploring Taiwan in general and learning the local cultures there. On a personal level, I am interested in taking scenic photography, learning the history and trying out local cuisine.

Explainer: What's a monocyte monolayer assay?

To predict whether a red blood cell transfusion is compatible, a laboratory test is used to see whether the patient’s antibody will react to donor’s red blood cell antigens. For some patients with antibodies, it can be very difficult to find compatible blood, and often the only choice is to transfuse the “least incompatible” blood. But how do you make that choice?

Unfortunately, looking at antibody-antigen reactions alone cannot predict whether the patient will have a clinically important reaction. This is because antibody binding is just the first step in a complex process in the body that leads to the red blood cell destruction (hemolysis) that can make the patient sick after an incompatible transfusion.

The “monocyte monolayer assay” is used to better predict the risk of a clinically significant reaction. Developed in 1976, this cell-based assay helps determine the risk of transfusing antigen-positive red blood cells to a patient who has an antibody or antibodies against the antigen(s).

How does it work?

Monocytes, the immune cells that destroy red blood cells during an adverse transfusion reaction, are isolated and placed in a single layer on a plate in the laboratory. The donor red blood cells are mixed with the patient’s antibodies and added to the monocytes.

Under a microscope, the number of monocytes with one or more red blood cells adhered/engulfed at the end of the assay is counted and this is used to calculate a “monocyte index”. If the monocyte index is less than five per cent, this indicates that the red blood cells won’t be rapidly destroyed and that the patient won’t have a serious reaction to the blood. Using this assay can accurately predict whether transfusing the red blood cells will lead to a clinically significant reaction, helping to make the safest choice for the patient.

Canadian Blood Services – Driving world-class innovation

Through discovery, development and applied research, Canadian Blood Services drives world-class innovation in blood transfusion, cellular therapy and transplantation—bringing clarity and insight to an increasingly complex healthcare future. Our dedicated research team and extended network of partners engage in exploratory and applied research to create new knowledge, inform and enhance best practices, contribute to the development of new services and technologies, and build capacity through training and collaboration.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services nor do they reflect the views of Health Canada or any other funding agency.

Related blog posts

Wonder drug it may be, but IVIg is a slippery fish. Even after 60 years, little is known about precisely how it works. An encounter with a scientist The first thing you notice when you walk into Dr. Don Branch’s office at 67 College Street in Toronto is how small it seems. And colourful, owing to an...

When a person is in dire need of blood, a blood transfusion seems like a simple solution. A donor donates blood, and eventually a patient in need receives it. Yet, in reality this life-saving medical procedure, as safe as it may be, is not that simple.