By analyzing donated blood, we’re helping to shed light on the state of COVID-19 in Canada

Through the pandemic, our seroprevalence research has aided public health decision-making

In April 2020, when the federal government established the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force (CITF), Canadian Blood Services moved quickly to help by providing a critical source of insight: data on the levels of COVID-19 antibodies found in donated blood across the country.

Two years on, we’ve tested close to half a million blood samples from donors to support what has become one of the largest-ever national studies of seroprevalence — the level of immunity to a specific pathogen within a population, based on analysis of blood serum. (Quebec’s blood operator, Héma-Québec, has also been providing data for the study.)

“By the end of that first pandemic summer, in 2020, we were seeing hugely important findings,” says Dr. Timothy Evans, executive director of the CITF Secretariat. Although provinces at that point were still testing widely for COVID-19, it wasn’t clear how many infections were potentially being missed, including in people without symptoms. The seroprevalence data helped fill in the picture, revealing that very few Canadians had in fact been infected with COVID-19. This spoke to the success of public health measures, but it also signaled to officials facing an expected autumn surge that they could not count on widespread immunity from past infections to blunt its impact.”

“Some people had been suggesting that as much as 30 or 40 per cent of the population might already have been infected, when in fact it was less than 1 per cent,” explains Dr. Evans, who is also the inaugural director of McGill University’s School of Population and Global Health.

“This made clear that there was a lot of dry tinder for a second wave.”

As the second wave of COVID-19 spread in the fall of 2020, Canadian Blood Services seroprevalence data showed that overall infection rates remained well below 5 per cent of the adult population. And when vaccines became available in early December, the study data continued to reveal low levels of infection-acquired immunity.

“It was abundantly clear to policymakers that the only route to herd immunity was to rapidly role out the vaccines,” Dr. Evans says. “And that’s what Canada did.”

An extraordinary team effort

Blood testing and analysis for the seroprevalence study are conducted at Canadian Blood Services headquarters in Ottawa — in an existing lab that was actually being dismantled when Craig Jenkins, a veteran medical laboratory technologist and technology consultant with our innovation team, was asked to transform it for the new initiative.

By analyzing samples of donated blood across the country, Canadian Blood Services scientists have helped to track the spread of COVID-19.

“I love a challenge, I think sometimes to my own detriment,” Craig says with a laugh. “I truly believe if you put your mind to it and you have the right approach, you can do anything.”

Craig and a team of colleagues from across the organization marshalled equipment and staff and set up the necessary processes, working with a speed that impressed the study’s principal investigator, Dr. Sheila O’Brien.

“Normally it would take six months or a year of planning and getting things in place,” says Dr. O’Brien, who is our associate director of epidemiology and surveillance. “They had a lab set up in a month.”

Craig credits this remarkable achievement to the spirit of collaboration that is one of our organization’s defining values.

“There were a lot of moving parts, right down to the facilities folks running electrical wiring for us, changing the plumbing and moving around whole pieces of the lab. It really was a team effort.”

In the first week of testing, Craig was joined by a dedicated group of colleagues — including Dr. Chantale Pambrun, our senior medical director of innovation and portfolio management — as everyone clocked 14-hour days to meet an initial target of 10,000 samples.

Since then, resourceful teamwork has kept the data flowing despite a wide range of challenges, from a tight job market for additional lab staff to a global shortage of pipette tips.

When one of the lab’s freezers failed, putting blood samples at risk, the Ottawa logistics team managed to save the day by securing a refrigerated truck.

Tracking the vaccines’ impact

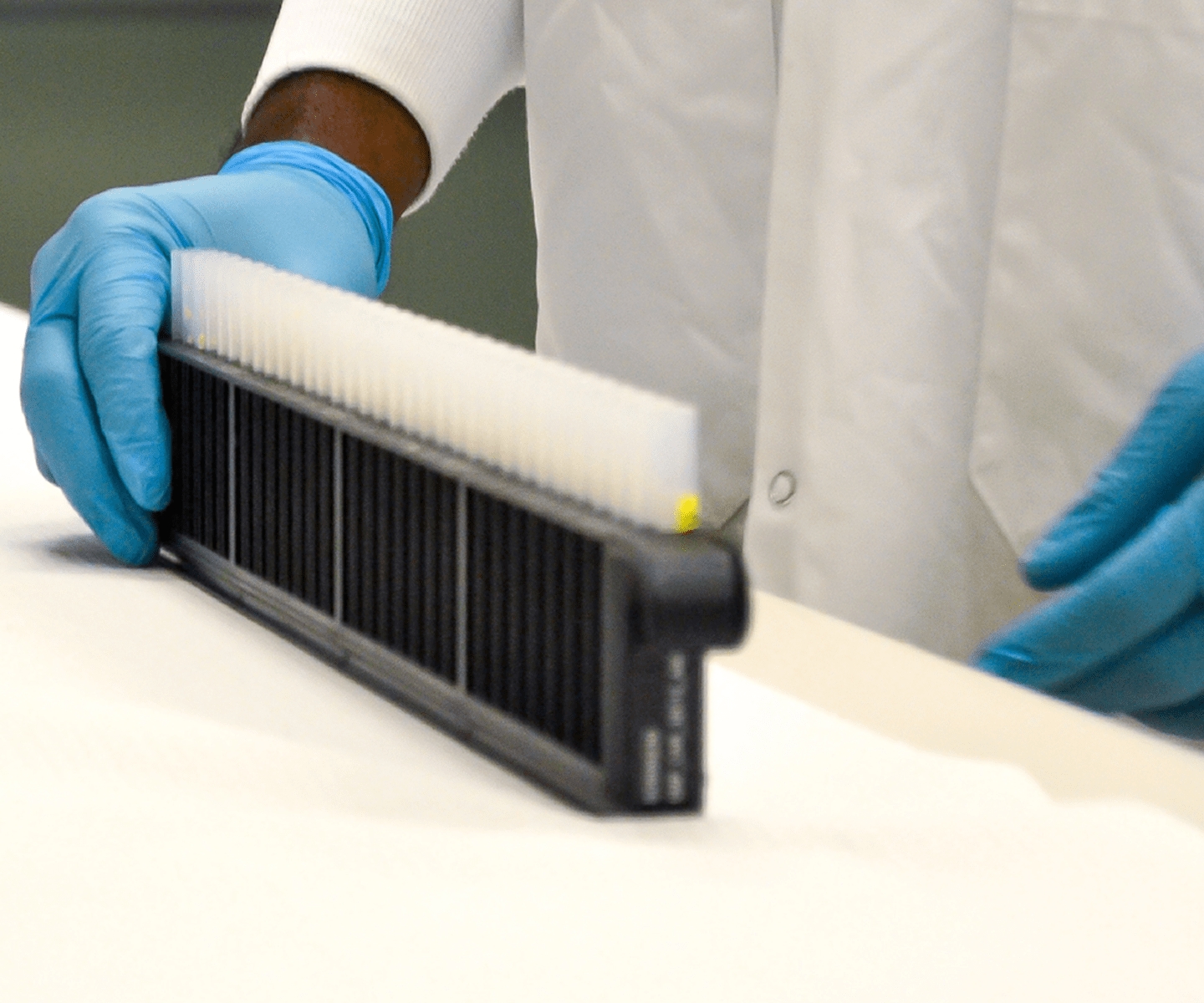

Blood samples from donors arrive at the lab from all over the country (excluding Quebec and the northern territories) via Canadian Blood Services testing facilities in Calgary and Brampton.

After lab personnel test for COVID-19 antibodies, information specialists combine the results for each sample with anonymized data on the corresponding donors, including age, sex, ethnic background and location. Dr. O’Brien’s team then draws on that data in preparing regular reports for the task force.

The arrival of vaccines beginning in late 2020 was naturally cause for celebration across Canada. But it also posed new challenges for the study. Our initial testing methods and equipment could only detect antibodies generated by infection.

As vaccines were administered, we needed to keep tracking immunity acquired via infection while also measuring the antibodies arising from vaccination. This meant reconfiguring the lab to install new analyzers, as well as updating procedures for staff.

The continued flow of data on infection-acquired antibodies proved especially valuable from late 2021 onward, as COVID-19 cases skyrocketed (mainly from the Omicron variant) even as the rate of community testing plunged, with the result that only a tiny fraction of infections were being recorded.

While some monitoring of COVID-19 has been maintained through wastewater sampling, the ongoing seroprevalence study has enabled far more accurate estimates of the actual number of infections.

“Data from blood donations has become more important than ever in the context of Omicron, which has simply overwhelmed acute infection testing systems,” Dr. Evans says.

As the seroprevalence study has increased reporting frequency from monthly to every two weeks, the data reveals that nearly 50 per cent of Canadians have been infected during the Omicron wave. We’ve entered a new era of hybrid immunity.

Identifying larger patterns of COVID cases in Canada

Combining blood sample analysis with other donor data has also helped illuminate the bigger public health picture. “We’re now able to link differences in infection rates to key social determinants of health,” Dr. O’Brien explains.

“We’ve seen, for example, that racialized donors are more likely than white donors to have been infected with COVID-19. The same is true for donors who live in more materially deprived neighbourhoods.”

The next stages of this work promise even richer insights if COVID-19 antibody levels can be linked to other health information (in jurisdictions where such data is available — as always, using secure methods that protect donors’ privacy).

This could include details of the donor’s COVID-19 vaccination history, the timing and brand of each vaccine dose, and any history of infection confirmed by lab testing. “It opens up many very interesting opportunities to better understand people’s immunity generally,” Dr. O’Brien says.

In an increasingly complex pandemic environment, this evolving data stream could help inform decisions about when to provide more boosters and to whom. “If people have had three vaccinations and have also been infected, do they need a booster?” Dr. Evans asks.

“And if so, when? Understanding the number of infections in the population and their distribution — for example, we’ve seen higher prevalence among younger age groups — is going to be really important as we think about the best strategies for managing risk.”

Beyond COVID-19

The national seroprevalence study was initially scheduled to conclude in the spring of 2022 but has now been extended to at least 2023. It has also opened up new potential areas of inquiry as the pandemic gradually recedes.

“The recognition of the role that blood donors and Canadian Blood Services can play in public health surveillance happened all at once in 2020,” says Dr. O’Brien. “And it’s been a springboard for the idea that we could have an ongoing role, even after the pandemic.”

Dr. O’Brien explored this possibility further in a recent journal article co-authored with Dr. Steven Drews, a microbiologist on our research team, and scientists from other organizations.

They noted that each time a donor gives blood, an extra tube is collected in case additional testing is required. But because only about 20 per cent of those samples are ever needed, the rest can be made available for other purposes (as has been the case for the seroprevalence study).

For example, they could be used in surveillance of other vaccine-preventable infections. Or they could allow scientists to track emerging pathogens spread by animals or insects — an especially important area of investigation as climate change affects habitats.

Test results from the extra blood tubes could also be combined with information obtained through routine donor screening, such as hemoglobin levels, current medications, recent vaccinations, travel history and more. And because about 90 per cent of our donors give blood repeatedly, they could form a cohort to be monitored over time.

In addition, we’re exploring the feasibility of collecting additional health and lifestyle data through voluntary donor surveys, which could yield powerful new insights when overlaid with health registry data.

“Every society needs blood donors and blood collection services,” Dr. Evans sums up. “As long as they’re going to be a fixture in our institutional landscape, I think we could be much more creative and resourceful in how we harness their potential.”

This story is featured in our 2021–2022 annual report titled How We Connect. it’s one part of a larger chapter on research and innovation. Read more on this topic (including an interview with Dr. Isra Levy, vice president, medical affairs and innovation) and many other aspects of Canadian Blood Services’ work this past fiscal year.